On Skepticism: Its Definitions and Scope

Several people have asked me if I plan to respond to PZ Myers, considering the “beating” he gave me and others in a post last week.

Several people have asked me if I plan to respond to PZ Myers, considering the “beating” he gave me and others in a post last week.

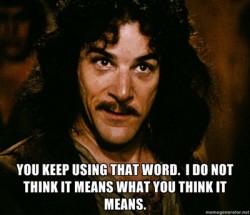

No, I don’t. I may if I see a good reason, but the truth is that responding to him is a bit like debating a creationist. Sometimes one should, but this is not one of those times. In this case, PZ has so grossly misrepresented my writings and statements that it is very clear that no productive discussion can occur with him on the matter. This is not the first time he has done so and not the first time that I have essentially ignored it. The post is almost entirely built on mischaracterizations, straw men, and falsehoods. If anyone else wants to discuss it, I will be happy to do so after you have read what I actually wrote, context and all.

Instead, I think that this is a good time to gather some of the more recent materials on the matter in one place because I strongly believe that most of the discussion in the general community over these issues involve new members trying to get a handle on what we’re all about. So, I will summarize my views on the matter in a few bullet points and provide a list of links to posts, publications, and videos what are free to all.

I will not be discussing tone and approach, but some of the materials do touch on this issue. I disagree with Novella and a few others on that question and it is always a discussion worth having, but separately.

As always, I welcome comments, but ask that if you plan to leave a comment arguing against my stance, please look through the links and read/watch those which appear to address your argument before you do so. I really hate repeating myself, especially when I have written what I think is a clear explanation, so I am quite likely to respond by referring you to one of the links.

A summary of my position and opinions on the issues:

- Skepticism, secularism, humanism, and atheism (as an issue for activism, not a conclusion) are distinct ideologies with differing central values. These distinctions are important for several reasons, including organizational focus, communication, and personal objectivity. Those are covered in more detail in the materials linked.

- Many people have adopted more than one of these ideologies (I, for example, have adopted all of them to some degree), creating a “greater” community we tend to refer to as the “rationalist” community. Not all community members have adopted all ideologies.

- Activism is about goals, and organizations form around specific goals to promote specific ideologies. Although the “greater rationalist community” shares a few core values, most importantly a naturalistic world view, each organization uses its resources in different ways, supporting different priorities.

- Central to one of these ideologies, atheism, is the conclusion that there is no higher power (god). The ideological part is the value that belief in a higher power is harmful. There is more to atheism than that and I will not outline how it differs from secularism, etc., but these points are important because conflation of the conclusion with the value is one source of conflict.

- At the core of scientific skepticism is the view that evidence-based reasoning is the best way to decide what is and is not true. Furthermore, the only legitimate way to acquire evidence is through the scientific method, which is basically a combination of systematic observation (empiricism) and reason. Therefore, scientific skepticism involves using the scientific method to test claims.

- The major Skeptic organizations have expressed missions to promote scientific skepticism. They do so for a number of reasons, both epistemic and pragmatic, most of which have been discussed at length in past days, weeks, months, years, and decades (and so on).

- From a “best practices” standpoint, skepticism reaches more people by focusing its efforts on testable claims because it can include those people who have not adopted one or more of the other ideologies I mentioned (e.g., atheism).

- From a philosophical standpoint, science is a method for acquiring knowledge, all of which is tentative. Because nobody knows with absolute certainty what is true, the method is much more important than personal conclusions. The method is how we can convince other people that our conclusions are accurate.

- Also from a best practices standpoint, promoting methods (which includes sharing evidence and information such as alternative explanations for events) provides people with the tools to evaluate other claims more effectively.

- From both a philosophical and best practices standpoint, promoting personal conclusions rather than method is a violation of basic scientific tenets and logic. Likewise, when we judge a person’s ability to use methods based solely on their beliefs (e.g., statements such as “Christians are not good skeptics”), we are judging an argument by its conclusion and not the merits of the argument itself. This is not scientific at all. Ironically, it’s bad skepticism.

- Skepticism activists do promote some conclusions, such as the conclusion that vaccines are relatively safe and effective, however, we do so with great care. Where scientific consensus is weak or lacking, expertise and personal responsibility is vital.

- Objectivity is a central feature of scientific thinking and, therefore, of scientific skepticism. Although no human being is purely objective (arguable, but I think most of us agree), one of the main purposes of the scientific method is to remove subjectivity from the inquiry process. In practice, it’s imperfect, but if we throw our hands up on this issue because scientists are not unbiased, we must reject science altogether. It’s that central.

- Because objectivity is central to skepticism and values such as political ideologies should not drive the practice of skepticism or science, but should be informed by the findings of science and skeptical inquiry (e.g, science cannot tell us if gun control is good, but it can tell us if a specific regulation is likely to reduce the number of deaths by gun). In other words, economy, religion, and feminism are not “off-limits”. They should be and are subjected to the same treatment that all other topics are subjected to. They appear to receive different treatment merely because the claims made in these areas tend to be more complex and more difficult to test (if they are testable at all). Furthermore, these topics tend to be attached to strongly-held values and, because human beings are notoriously tenacious in their beliefs, more controversial.

- The difficulties with discussions of complex topics makes internal agreement less common and without internal agreement, good outreach efforts are not possible because no coherent, unified message is possible. The goal of most activist organizations is outreach more than community and they are trying to maximize success, not put up roadblocks to it. Therefore, they tend to focus on claims which provide a more predictable and clear outcome.

I could get into more detail, but that isn’t my goal with this post. So, I will stop here. Following is a list of excellent materials which discuss, in one form or another, the scope of skeptic activism, its purposes, and its value.

Free Publications (these three should be required reading):

- Where Do We Go From Here? by Daniel Loxton – The most to-the-point discussion of why we do what we do, sometimes referred to as a skeptical manifesto

- What Do I Do Next? edited by Daniel Loxton – a collection of discussion about skeptical activism by leading skeptics

- Why Is There A Skeptical Movement? by Daniel Loxton – A two-part essay with highlights from the history of the movement and a practical discussion of scope

Blog Posts/Web Publications:

- Scientific Skepticism, CSICOP, and the Local Groups by Steven Novella and David Bloomberg – a primer on scientific skepticism and organizational scope

- Bigfoot Skeptics, New Atheists, Politics and Religion by Steven Novella – a response to PZ Myers and another blogger who suggested that skeptical activism needs to expand its scope

- PZ Replies by Steven Novella – a continuation of the dialogue with PZ Myers, responding to a reply in which Myers accuses several of us (myself included) of intellectual dishonesty and cowardice

- Scientific Skepticism, Rationalism, and Secularism by Steven Novella – more clarifications incorporating the discussions which followed the dialogue with PZ.

- Steven Novella Steven Novella Takes on Some of the Oldest Clichés About Scientific Skepticism-Again by Daniel Loxton – more on the conversation between Novella and Myers

- You May Be Forgiven For Thinking That Some Skeptics Are Taking A Firm Stance, But… by Kylie Sturgess – more on the conversation (and a reiteration that the arguments are not new) with added emphasis on the importance of educating one’s self before criticizing

- Further Thoughts on Atheism by Daniel Loxton – discusses the need compartmentalization of concepts (atheism and skepticism), mostly for pragmatic reasons

- The Surprising Twists of TAM9’s Diversity Panel by Daniel Loxton – discusses the way that a focus on methodology allows for a more inclusive group

- The Conflation of Atheism and Skepticism: Fact or Fiction? by Kylie Sturgess – a discussion of the problems with confusing methods with conclusions

- Skepticism and Religion – Again by Steven Novella – a reminder of the reasons behind mission focus and what it does and does not mean in terms of how skeptics approach religious claims

- A Few Comments on the Nature and Scope of Skepticism by Jim Lippard – a discussion of the problems with conflating skepticism with atheism and assuming that one leads to the other. This blog contains a large number of posts on scope, many of which are linked in this post, so I will only link to this one, but I highly recommend browsing through them

- On the Scope of Skeptical Inquiry by Massimo Pigliucci – discusses the relationships among philosophy, skepticism, atheism, etc.

- What Is Skepticism, Anyway? by Michael Shermer – also includes a video, so it’s listed twice here

- Is There a New Atheism at the JREF? by D.J. Grothe – a response to accusations that the JREF’s mission might be shifting with an emphasis on the organization’s priorities

- Media Guide to Skepticism by Sharon Hill – Sharon worked with community leaders to produce a summary of the purpose and scope of organized skepticism.

- Blog post by Daniel Loxton introducing a video of a panel at TAM 2013.

- John Horgan is “Skeptical of Skeptics” by Steve Novella

- Bigfoot Serses the Quest for World Peace? by Daniel Loxton

Posts on this blog:

- Take Back Skepticism Part I: The Elephant in the Room – The first in a three-part series about the scope of skepticism, tone, and arguments about both

- Take Back Skepticism, Part II: The Overkill Window – the second in a three-part series which focuses on the propogation of hate and irrational arguments about tone and scope

- Take Back Skepticism, Part III: The Dunning-Kruger Effect – the third in a three-part series which focuses on overconfidence and anti-intellectualism displayed during arguments about scope

- Paved With Good Intentions – about the dangers of allowing values to drive the process and interfere with objectivity

- Why the “Critical” in Critical Thinking – covers the basic falsification approach in science and critical thinking to explain the purpose of critique

- You Can’t Judge an Argument by Its Conclusion – describes the Belief Bias (a form of Confirmation Bias) and explains why judging a person’s ability to reason based on their beliefs is fallacious (ironically)

- Mission Drift, Conflation, and Food For Thought – discusses some of the dangers of “mission drift” and attempting to add values such as political ideologies to organizational missions

- What Matters – a response to the misguided view that skeptical activism does not focus on things that matter

- Scientific Skepticism: A Tutorial – about definitions and scope

To watch/listen

- Overlapping Magisteria, TAM2012 – Jamy Ian Swiss talks about the importance of mission focus, the value of the work that skeptics do, and the reason we value methods more than conclusions

- Skepticism is a Humanism, NECSS 2010 – D.J. Grothe’s keynote, which discusses the scope of skeptical activism, noting that, although it is methods-based we are motivated to activism by humanist values

- On the Ledge, Skeptrack at Dragon*Con 2011 – A panel discussion with Eugenie Scott, Margaret Downey, D.J. Grothe, and me, moderated by Derek Colanduno about the overlap of atheism and skepticism, its challenges, advantages, and pitfalls. Ideology is discussed about half way through

- What Is Skepticism, Anyway? by Michael Shermer – also includes a blog post, so it’s listed twice here

- Skeptical Scope and Mission, a panel at TAM 2013 with myself, Daniel Loxton, Steven Novella, Jamy Ian Swiss, and moderated by Sharon Hill.

- How To Be A Bad Skeptic, Q.E.D. – D.J. Grothe’s rundown on some of the dos and don’ts of skepticism. You’ll have to guess which parts are facetious and which are serious. By this point, you should be able to do this.

I will add to this post as new content becomes available, so if I have missed any that you think should be included (and it is freely available online), please contact me on Twitter or Facebook so that I can add them into the body of the post. I will also apologize now if I have missed something important. There has been so much discussion of this topic that I was a bit overwhelmed trying to put together just the highlights.

It seems to me that the “Social Justice” folks in the Skepticism “movement” (or the Skepticism circle of enthusiasts, if that’s a loaded word) are prone to begin with an answer, and then look for evidence to support their position, when it comes to the SJ issues they want Skepticism to wade into. But, because so many SJ issues require value judgments, what they’re demanding of Skepticism is the very antithesis of Scientific Skepticism.

This is exactly why I think Jamy Ian Swiss “you’re welcome to come into the tent, but don’t come in, and then announce you’re moving it” rang so strongly with me. Some appear to be interested in demanding movement towards whatever agenda they happen to support.

Underpinning all of this is a lucrative series of conferences, speaking fees, and influence, all of which drive up website traffic. The conferences serve as showcases for various speakers, many (all?) of whom will often have websites, blogs, or “brands” that will gain more influence and money from attention. So even if they money they receive for speaking isn’t that much, the conferences, blogs DISCUSSING those conferences, and word-of-online-mouth drive up influence (and website revenue). Of course there’s money to be made: Book deals, jobs with online magazines, etc. We’ve seen bloggers go to “full time activism,” giving up their day jobs. They still have rent/mortgages, and have to eat. Clearly, there’s money to be made. And these conferences wouldn’t keep going if they were LOSING money. The area is indeed lucrative.

The growing number of conferences is an indication that people have realized there’s money out there to be made, and every potential attendee who goes to Conference X may not have the resources to attend Conference Y. So, naturally, some competition starts to creep in for the “attendee dollar.” This motivates conference organizers to Balkanize, and declare themselves specially sensitive to whatever pet issues are out there (being too “moderate” will just mean that people will just attend well-established, or widely-reknowned conferences, so there is a motivation to find something to “set yourself apart” from the “old guard”).

The problem for the conferences is that the “old guard” is sitting on the moderate, science-only issue. There’s almost nowhere else to go BUT to spread out into Social Justice issues. Yet they have to maintain an air of Science about them, or else risk losing the credibility of the movement itself.

Whew, said a lot more than I expected. I need a tagline. Here goes: “Atheism should be about ‘Science and Social Justice’ the same what the Math should be about ‘Numbers and Fashion.'”

I completely agree, and that’s a very clear way of describing a big part of the problem, so thank you.

I think that problem is compounded by something that a lot of people don’t want to talk about (hence one of my posts is subtitled “the elephant in the room”) because it is a personal accusation. It is something that I have studied and I think it’s an important issue: overconfidence feeds this monster. Overconfidence is strongly correlated with entitlement; the more overconfident one is, the more entitled they feel to promote (and ask others to promote) their conclusions, and to do so in their own way. Since overconfidence is inversely related to real competence, those with lower entitlement attitudes tend to hold more accurate views and come to better conclusions.

It’s a vicious cycle.

On another note, the last line of your comment struck me. I don’t really care if atheism is about social justice. In fact, I wouldn’t care to support an atheist group that didn’t have a humanist mission. But skepticism is an entirely different story. It’s not about what we believe, but how we evaluate information (and about the amount and quality of the information we evaluate).

How silly of me — here I am discussing Scientific Skepticism, and then I shorten it in my last line to “Atheism.” A long time ago, I used to use them interchangeably, but I shouldn’t have. In fact, I’d pretty much welcome any and all theist Skeptics. For instance, I think Dr. Ken Miller is a wonderful ally, and he’s Roman Catholic. Fine by me, because he has no desire to teach RC in public schools.

Anyway. I guess this is me saying that I should proof my comments better. 😛

Good post. For what it is worth, I’d like to offer two thoughts.

“Skepticism, secularism, humanism, and atheism” seem highly non-parallel, and therefore, tending toward confusion. First of all, skepticism and humanism are processes for learning and dealing with life and each other. Atheism, even as an “issue for activism” and secularism are both responses to specific people’s magical thinking. They are not life processes. Thoughtful people must select processes related to skepticism and humanism, but one need never make decisions about beliefs held by others. Substitute “belief in Santa Claus” and “not allowing special roles in government for Santa Clausers” and try holding a-santaclausism and “santaclausers shall have no special role in governing us all” parallel with skepticism and humanism. There is no parallel. Long ago I quit discussing atheism as such and ask those who might want discussion to limit themselves to one topic at a time — “is there a god” requires a meaningful, testable definition of a god, “do miracles happen” requires a falsifiable definition, “does prayer work” requires experiment. Otherwise we might as well be talking about the existence of “fleendab”. In any other arena those requirements would be minimal and they should never be relaxed because the topic is theistic.

It seems to me that the two highly important behavioral issues of skepticism and humanism get short shrift when lumped with the peculiar topics of magical beliefs and empowering magical believers.

The other, minor thought is that I’d disagree that atheism requires either a belief that theism is harmful or that “there is more to atheism” than just an position that there is no credible evidence to support a belief in a god. Personally, as a not-a-theist, thats as far as I go. Any conclusions of the harmfulness of theism come from skepticism, the insight gained from a scientific approach to thinking. I don’t think not believing in Santa Claus requires any judgement about the harmfulness of telling children to believe in Santa Claus.

Thanks for reading.

In that section, I was referring to atheism as an activist endeavor, not a position. I’m sorry that wasn’t more clear. I think we are in nearly total, if not total, agreement.

A more pure definition perhaps: skepticism admits POSSIBILITY of knowledge as guessed re evidence etc while also accepting that new evidence MAY OVERTURN any claim.

excerpts from Karl Popper: philosopher of critical realism

by Joe Barnhart

Those who call themselves skeptics sometimes quote W. C. Clifford: “It is wrong, always and for everyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence.” Unfortunately, Clifford gives no rational hint as to how many pieces of evidence total up to being sufficient.

Furthermore, Popper’s epistemology makes no fetish of either skepticism or faith. I know of no one who practices either wholesale skepticism or wholesale faith. All believers in certain claims are skeptics about rival claims. And all skeptics regarding some claims are believers regarding other claims. All of us, however, have pockets in our lives in which we would be better off if we showed more faith or trust. At the same time, there are pockets in which we would be better off if we trusted less–or at least shifted our faith to something or somebody more trustworthy. Trust and faith, like skepticism, are essential ingredients to human living. Skepticism per se is neither the enemy nor ally of faith per se, for the simple reason that neither exists.

The beauty of Popper’s evolutionary theory of knowledge lies in its insistence that imagination and speculation are essential ingredients of the thinking process. Intuitions become a part of every variety of genuine thinking, including science, because they are accepted as trials rather than dogmas.

Most of our scientific intuitions and conjectures have proved to be unsatisfactory. But Popper argues that some falsified theories have contributed more to the growth of science than have safe, shallow theories that no one has bothered to falsify. Science needs fruitful and falsifiable hypotheses that not only venture into new territory but seemingly go counter to common sense. “Let your hypotheses die for you,” Popper proclaimed. His epistemology is truly liberating, saying in effect that we should not worry about our theories cracking or collapsing because there are always more where they came from.

Creationism and Evolution.

Creationists who insist on classifying their views as “scientific creationism” may not know what they are getting into. Do they really want to assert that creationism is falsifiable? Do they want to try to expose its weaknesses and flaws? Do they seek to correct and revise the doctrine? As is well known, creationists take great delight in pointing out that the theory of evolution is, after all, a theory. But this should pose no problem. All scientific theories are theories. Do creationists want to say that creationism is a theory? Do they want to say that the notion of the Bible as inerrant revelation is a theory?

If Popper’s analysis is correct, then both evolution and creationism are theories. The real question has to do with how well they are articulated, how well they serve to advance further research, and how well they survive rigorous criticism.

The overwhelming majority of biologists and anthropologists have found creationism to be a poor rival to evolution in the attempt to expand our knowledge. Contrary to what some creationists claim, scientists tend to favor evolution as an explanatory theory not because of some presupposition that blinds them to the truth but, rather, because it is scientifically more fruitful than creationism and enjoys greater explanatory power.

Just for fun, with regard to Clifford’s quote, and because I’ m not entirely sure Clifford didn’t mean the quote as a joke, dissecting his statement brings the following to mind.

In this context what does “wrong” mean? It seems, on the one hand, to mean moralistic (bad boy, bad boy!) or does it mean only not correct? Hopefully he didn’t stoop to moralism, but not correct hardly works, either. Often people believe something that turns out to be true based on the flimsiest of reasons. (Most of us believe Jupiter is bigger than Saturn although virtually no one has any evidence. The most compelling reason I can think of is, why would astronomy authors choose to lie?). Am I “wrong” to believe that there is intelligent life on another planet in this galaxy? I’d say the evidence is pretty “insufficient”, as in close to zero, as of today. Am I “wrong” to believe (want to believe?) that my one year old granddaughter will someday be really successful as a musician?

I posit he meant it as a joke because he uses “always and for everyone”. Absolutes, like the sign saying “don’t believe anything you read on a sign” usually are meant as humor…

The statement ,“At the core of scientific skepticism is the view that evidence-based reasoning is the best way to decide what is and is not true. Furthermore, the only legitimate way to acquire evidence is through the scientific method, which is basically a combination of systematic observation (empiricism) and reason. Therefore, scientific skepticism involves using the scientific method to test claims.”, makes some good points but also in my opinion some misleading points.

Joe Barnhart’s Clifford quote is in the context of demolishing the logical empiricist definition of knowledge as “justified true belief”.

There is no scientific method other than being vigilant to make all claims open to refutation by evidence. There is no clock-work mechanism to produce explanations, they can come from a dream, a conversation, a worrying problem, a cup of coffee, a fantasy, a poem and even an observation or many such. These explanations are guesses, albeit often very sophisticated guesses. Dressing up guesses as some sort of fail-safe logical procedure has filled more library books than were lost in the library of Alexandria.

The trouble is that the dogmatic “justified true belief” flavour that drifts into a lot of sceptical proselyting alienates the very audience that it is trying to reach – unless of course it, like other faiths, it is content to preach to the converted.

In my view, which is strongly critical rationalist in flavour, all of us are wrong but sometimes less so than others. Even when we are right we cannot be certain. That is science, and in my view it is empirical skepticism.

Empirical skepticism admits the POSSIBILITY of knowledge as conjectured concerning problems, evidence and so forth while also accepting that new evidence MAY overturn any claim.

Creationism is not science because its proponents tend to collect evidence only to justify it and they consistently wriggle out of making their claims falsifiable. Being falsifiable means being stated in such a way that evidence, if found, could refute it.

Futhermore, Karl Popper replaces the problem “How do you know? What is the reason or justification, for your assertion?” by the problem: “Why do you prefer this conjecture to competing conjectures? What is the reason for your preference?” One might consider internal consistency in comparing conclusions, investigations of the logical forms of theories, comparing theories with other theories to determine whether or not the theory under consideration is a scientific advance, and empirical applications of the conclusions.

Critical preference is critical, not justification of beliefs.

You seem to have read a LOT more into this post than is there, or perhaps you just didn’t read it all, because you’re doing into details which support what I summarized (I did say that it was a summary and provided a lot of links to details so that I wouldn’t need to discuss them in this post).

A more careful read might clarify things and show that you’re not arguing with me. You’re expanding on what I wrote. I don’t think that what I wrote is misleading at all. It’s a summary, with suggested reading for detailed explanations.

Good piece, Barbara. Honestly, I think it’s a bit sad that so much valuable time from smart people (such as yourself, Steve, and others) is being spent addressing issues that PZ brings up. I’ve long ago given up caring what PZ thinks, and he just feeds off “controversy.” Also, your comparison to debating creationists is spot-on.

There is much of great value and diligence in your blog. I was speaking more to the tendency of the skeptical movement overall to be non-skeptical and dogmatic. Which tires me. I would have thought my comments would have been useful for assisting a tightening of the armoury against pedlars of harmful pseudo-science fallacies.

Not ad hominem at all.

Part of the reason for the dogmatic drift in the skeptic movement is a subtle philosophical under-pinning of justificationism or foundationalism.

I would have thought that in the search for truth a critical to and fro would be welcome.

You did post as a “core” statement: “At the core of scientific skepticism is the view that evidence-based reasoning is the best way to decide what is and is not true. Furthermore, the only legitimate way to acquire evidence is through the scientific method, which is basically a combination of systematic observation (empiricism) and reason. Therefore, scientific skepticism involves using the scientific method to test claims.”

I do not think that we can decide what is true other than as a critical preference; a less wrong option.

We can acquire evidence or inspiration from all sorts of places… no method necessary.

I agree that scientific skepticism involves testing claims and using critical analysis.

The goal of science is problem solving and good explanations, and of course we would like them to be true.

It is, but you’d framed it as an argument when I saw only agreement.

Agreed, and I often note that I don’t think the word “truth” has a place in skepticism, so my choice of words here is poor.

In detail (a simplified version of what you wrote), science’s ultimate goal is truth, but it recognizes that such a thing is not entirely possible. So, when I say that we use X to decide what is “true”, I refer to the goal. It’s a shorthand that I really should try to reword.

As Sam Harris put so well: …shepherd of Internet trolls PZ Myers…

http://tinyurl.com/c8k3tlk

And you’re right. He (Myers) does argue like a creationist.