Fun Does Not Sell Smarts

Each semester I teach at least one course with a co-requisite laboratory course in which students conduct psychological research in small groups. Due to certain requirements of the American Psychological Association, these studies are not eligible for publication in an approved journal. Although students sometimes meet the requirements and re-run these studies in order to present or publish the findings, the original studies are considered pilot studies.

Some of these studies are very well-designed and executed and the findings are often interesting new discoveries. So, I have decided that it is about time I shared some of them and I will begin today with a timely finding about impression formation.

This semester, Brittany Reid, Lisa Aguilar, and Nare Setyan were interested in factors involved in judgments of intelligence and credibility as applied to marketing and image management. Specifically, they wondered if a hedonistic culture (party attitude) promoted by a group resulted in lower judgments of intelligence and credibility than traditional cultures. In other words, if you advertise that you like to party, will people think that you are less intelligent?

There is very little in the scientific literature regarding the assumptions people make about the relationship between hedonic behavior and intelligence. In fact, we could find none. There are mixed findings regarding the factors involved in judgments of intelligence. Most find that men are judged more intelligent than women, although no practical sex differences exist in general measures. Some studies have found that unattractive men are judged as more intelligent than attractive men and that the reverse is true for women. Many studies have found the opposite. Some have even suggested that attractive people are judged as more intelligent than unattractive people because they are more intelligent.

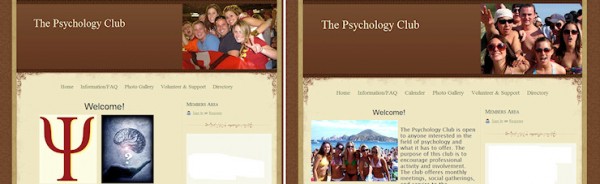

One club, two websites: a traditional academic site (left) and one which emphasizes a 'party' attitude (right)

We know that the way people dress, the number of piercings, the number of tattoos and all sorts of other things affect our judgments of people’s intelligence, competence, and a host of other attributes. The truth is, in the absence of other information and in some cases even when explicit information (e.g., about intelligence) is provided, appearances matter. So what about behavior? How does that affect the impressions people form of others?

The researchers hypothesized that the creators of a hedonistic (party attitude) group are judged as less intelligent and less credible than those of a traditional group. To test this hypothesis, they created two websites for a university psychology club.

Appeared on the home page of both versions.

- The main photo on the front page was clearly taken at a party whereas the main photo on the traditional front page was a group of students.

- The “spring break” photo gallery contained photos of parties and women in bikinis and people drinking at parties. The same gallery on the traditional site contained photos of students building houses for a charity. The events galleries included similar, but more subtle differences in the activities depicted.

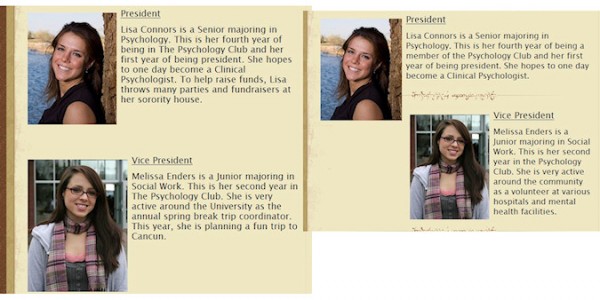

- The executive board’s biographies focused on casual attributes whereas the traditional board’s bios discussed science.

Participants (28 of them; the responses of men and women did not differ in any of the measures) were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions. They were instructed to study the website for 5 minutes and that they would be asked to remember it later. Afterward, they navigated away from the website and completed a survey about the site. They were asked to indicate the degree to which they agreed with each of 10 statements using a 5-point Likert scale. The statements were:

- There should be more sites of this nature.

- This website promotes education.

- I would visit this website again.

- This website promotes “a good time”.

- I would recommend this site to others.

- I trust this site for credible information.

- The creator of this website is intelligent.

- This site is boring.

- I would view this site in my own time.

- I learned something new from viewing this website.

I will not bore you with the statistical output, but for those interested, I will note the following: The hypotheses were tested though independent samples t-tests comparing the judgments for numbers 6 and 7, then responses to all questions were also compared. The additional analysis is exploratory, but adjustments to alpha would only change the outcome of #10, which resulted in a p-value of .01. All other p-values are less than or equal to .001.

The findings are best illustrated by listing the agreements which did and did not differ among the groups. Tests of the research hypotheses appear in bold. The largest difference was in responses to question number 1:

| Traditional Site Rated Higher | No Difference |

|---|---|

| 1. There should be more sites of this nature. | 3. I would visit this website again. |

| 2. This website promotes education. | 4. This website promotes “a good time”. |

| 5. I would recommend this site to others. | 8. This site is boring. |

| 6. I trust this site for credible information. | 9. I would view this site in my own time. |

| 7. The creator of this website is intelligent. | |

| 10. I learned something new from viewing this website. |

So, the presence of a ‘party attitude’ did not affect evaluations of the site itself. The traditional site was not considered more boring and participants were no less likely to visit it than the ‘party’ site. Surprisingly, agreement on whether the sites promote ‘a good time’ did not differ, either.

However, the traditional site produced higher ratings of education promotion and participants were more likely to say they learned something from it. Participants were more likely to recommend the site to others and feel that more sites of its nature should exist.

Most importantly, however, are the research hypotheses themselves, which address the views that participants held about the website’s creators and the credibility of the information on the site. Clearly, the creators of the ‘party attitude’ site were judged as less intelligent than the creators of the traditional site. Of course the reasons for this are not clear in this study. Participants may not have felt that people who party are less intelligent, but rather that people who chose to emphasize this behavior on a site promoting an academic (and science-related) club were less intelligent. This is a testable hypothesis, just not tested here.

What is most concerning for this context, however, is the difference in credibility. The purpose of the club as described on the websites is, “To encourage professional activity and involvement.” The goal is not to form a social club. Of course the images of partying are not contradictory (even on the traditional site, the images involve groups having fun), but they do not promote the cause. These seemingly unrelated endeavors (academic and hedonic) appear to mix like oil and water and for a university club wishing to promote a scientific field, credibility is vital.

There are some things to keep in mind when drawing conclusions from these findings. Some of these strengthen the argument, some are limiting:

- Participants only viewed one website. They did not compare the websites side-by-side. This is a strength as participants were given no clues to the purpose of the experiment.

- This was a true experiment and, therefore, causal conclusions are reasonable.

- Everything is relative and when we discuss scientific findings, we are always talking about comparisons. A medication works relative to no medication. A teaching method is better than a different method. In this case, the traditional academic website is compared to one in which relatively more images and verbiage referred to leisure social interactions (parties).

- The participants were college students in a science field. The proportion planning to work in the field is probably a minority (it changes) and the proportion planning a career in research is very small. Many students major in psychology without awareness of the scientific rigor required for a degree. Still, the participants of this study have been trained in research methods and there is some reason to think that they may care more about science and academics than the general public. I am not sure this fact is important when considering the implications, but it may be.

- There were some mistakes which resulted in unintended differences between the websites. For example, on one, the biographies are aligned vertically and on the other, one is offset to the right. There is a link to the calendar at the top of one and not the other. The gallery links are in a different order. I agree with the researchers that there is no reason to think that any of these minor differences affected the results.

That just about sums up the experiment. I leave it to you to decide what these findings suggests about impression formation and management in other pursuits and fields. Certainly they are not generalizable to every situation, but they do provide food for thought.

Fascinating! It’s nice to see some empirical evidence that’s in line with my own (anecdotal) experiences.

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Barbara Drescher and Barbara Drescher, Tonya K. Tonya K said: RT @badrescher: ICBS Everywhere: Fun Does Not Sell Smarts http://cli.gs/JHEMV | Definitely food for thought! […]

[…] Everywhere: Fun Does Not Sell Smarts ICBS Everywhere: BS for George Takei Fans and Consumers ICBS Everywhere: There Must Be an Idiom […]

[…] Everywhere: Fun Does Not Sell Smarts ICBS Everywhere: BS for George Takei Fans and Consumers ICBS Everywhere: There Must Be an Idiom […]

[…] Everywhere: Fun Does Not Sell Smarts ICBS Everywhere: BS for George Takei Fans and Consumers ICBS Everywhere: There Must Be an Idiom […]

[…] Everywhere: Fun Does Not Sell Smarts ICBS Everywhere: BS for George Takei Fans and Consumers ICBS Everywhere: There Must Be an Idiom […]

[…] Everywhere: Fun Does Not Sell Smarts ICBS Everywhere: BS for George Takei Fans and Consumers ICBS Everywhere: There Must Be an Idiom […]

[…] Everywhere: Fun Does Not Sell Smarts ICBS Everywhere: BS for George Takei Fans and Consumers ICBS Everywhere: There Must Be an Idiom […]

[…] Everywhere: Fun Does Not Sell Smarts ICBS Everywhere: BS for George Takei Fans and Consumers ICBS Everywhere: There Must Be an Idiom […]