Marmite Messiah and a Collection of Pareidolia

Posted May 28, 2009

Claire Allen holding the lid of a marmite jar with what she believes is Jesus's face.

Once again the son of God has appeared in food form, this time to a family in South Wales.

The mother, Clair Allen, discovered the apparition and the entire family agrees that it is Jesus.

Phil Plait disagrees. He says it’s clearly Derek Smalls of Spinal Tap, and I am inclined to agree. I think that says more about how close the Bad Astronomer and I are in age than anything else…

I thought I would take this opportunity to draw attention to a new set of static pages here at ICBS Everywhere and discuss the psychology behind these sightings, and why people will travel hundreds of miles and stand in long lines just to catch a glimpse of something which looks like something other than what it is.

At the top of the blogsite and in the upper left you will find links to static pages. One of those links, “Fun for Everyone” currently contains a link to a collection of simulcra — things that look like other things (go to the bottom of that page for links to more images).

Marmite Messiah

Apophenia is a term used to describe a number of common human behaviors including illusory correlations (the root of much superstition), probability matching, and pareidolia. This term generally refers to the human tendency to perceive meaningful patterns in random data, or data which are not consistent with the perception.

Pareidolia (puh-ry-dough-lee-uh) is the tendency to perceive familiar objects or pattern in unrelated stimuli. It occurs because humans naturally seek familiar patterns to help us to identify objects in the environment.

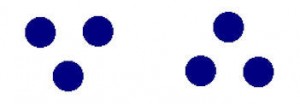

For example, something as simple as a colon followed by the letter “P” is perceived as a person with their tongue sticking out ( : P ).This tendency develops with experience, but there are some images, such as faces, for which we appear to have an innate preference. Infants exhibit a preference for faces just minutes after birth. They will stare longer at a face-like configuration of dots than they will the same dots in a different configuration.

Infants will stare longer at the configuration on the left than they will the right (Goren, Sarty, & Wu, 1975)

This is not surprising; we have specific brain areas devoted to the processing of faces. Faces are extremely important for the survival of social creatures like us, so we “see” them everywhere. It seems, however, that whenever a “face” appears to be male, we assume it is Jesus and when female, the Virgin Mary.

There are several websites with photo galleries illustrating this tendency. One of my favorite examples of face pareidolia is an extremely creepy tree posted in a forum by Matthew Ward of Cookeville, TN.

Miracles

When we attribute deeper meaning to the perception, as often occurs when images appear to be religious apparitions, we do so as a result of several factors, including the human tendency to misunderstand randomness. For example, if I offered you the choice of one of the following four lottery tickets, the lottery involving 6 numbers chosen at random from the numbers 1 through 40, which would you choose?

| Ticket A: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Ticket C: | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 35 | |

| Ticket B: | 7 | 12 | 19 | 23 | 33 | 37 | Ticket D: | 21 | 24 | 26 | 27 | 29 | 31 |

Would you think I was crazy if I chose A?

When I ask this question of students at the beginning of each semester, almost everyone chooses Ticket B. The reason most often given goes something like this: “It is more random, and the numbers are chosen randomly, so I would have a greater chance of winning.” Some say, “It is more spread out, so I have a better chance of winning.”

The truth is, the probabilities of winning with each of these tickets is identical. Since most people choose the numbers they will play, choosing ticket A makes it unlikely I will have to share a jackpot if I do win. Note, however, that my chance of winning is the same as with any other ticket: 1 in 3,838,380 (a sucker bet).

Random distribution does not mean a “spread out” or “even” distribution. Truly random data will have clusters and runs. However, humans are designed to recognize patterns, so when they appear in random data the data do not seem random. A experimental finding called probability matching illustrates this perception.

Participants are asked to predict which of two locations a target will appear. They are told (or learn through practice) that the location is chosen at random with a probability greater in one location than the other (e.g., 70% at location “A” and 30% at location “B”). The typical participant will distribute their predictions in a way which matches this distribution (e.g., they chose location “A” in 70% of the trials). The optimal strategy, however, is always to choose the location with the highest probability. However, when the sequence of target appearances is altered so that the distribution is more even, participants use the optimal strategy. Once patterns which appear by chance are removed from the sequence, it appears random.

To reiterate, in our efforts to understand the world, we look for patterns. What’s more, we look for meaning in those patterns. Combine that tendency with the tenacity and desire to believe in a supernatural guardian, and you have thousands of people flocking to office buildings, churches, trees, restaurants, and convenience stores to be closer to a sign from God.

The confirmation bias, a tendency to notice and remember more of the things which confirm what we already believe than things which do not, takes over. We evaluate claims based on what we think or wish to be true, rather than the merits of the claim itself. If you believe that miracles happen and if you want to believe that God, Jesus, or the Virgin Mary will protect you from harm or suffering, there is no work to do. Your brain is designed to accept these things as true.

The only thing standing between you and perceived salvation is rational thought, which is pretty hard work.

References:

Goren, C. C., Sarty, M., & Wu, P. Y. K. (1975). Visual following and pattern discrimination of face-like stimuli by newborn infants Pediatrics, 56, 544-549

Miller, M. B., Valsangkar-Smyth, M., Newman, S. E., Dumont, H. & Wolford, G. (2005). Brain activations associated with probability matching Neuropsychologia, 43 (11), 1598-1608 DOI: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.01.021

Wolford, G., Newman, S. E., Miller, M. B., & Wig, G. S. (2004). Searching for patterns in random sequences Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 58 (4), 221-228

Comments for this page are closed.